Chapters

- 1. Height and weight

- 2. Uses of the SI

- 3. Numbers and letters

- 4. Plain geometry

- 5. Circles

- 6. Compound interest

- 7. Population growth

- 8. Solid geometry

- 9. Molecules

- 10. Radioactive decay

- 11. Pressures

- 12. Gene frequency

- 13. Energy

- 14. Summary

Sections

Metric System (SI)

In science and medicine, measurements are always in metric-system units. In business and industry, the size of a product is almost always in these same units. For example, a tube holds 170 g (grams) of toothpaste, a box contains 491 g of bran flakes, a bottle of rum has a volume of 1 L (liter), a bottle of shampoo 400 ml (milliliters).

The Systeme International d'Unite's (SI) originated in France with the ''metre'' about 200 years ago. In an effort to make weights and measures more rational, the meter was defined as one ten-millionth part of a quarter meridian. A quarter meridian is the distance along a direct line from Equator to North Pole; in other words, the meter was intended to be a definite fraction of the circumference of the earth. Current geography indicates that the earth is not exactly spherical, but has an equatorial circumference of 40 075 240 meters, and a polar circumference of 40 008 082 meters. Dividing the latter by 4 gives a quarter meridian of 10 002 020 meters. Thus, the modern meter, based on atomic data, is a bit short, but extremely, almost incredibly, close to the ten-millionth part that the French scientists intended.

The beauty of the SI is that it is completely decimal, that is, based on 10. There are no units that are 3, 4, 12, 16, or 20 times another. The kilometer is 1 000 meters; the kilogram is 1 000 grams; 1 000 millimeters (mm) make 1 meter, and 1 000 milligrams (mg) make 1 gram. To go from one size unit to another requires only counting off places and moving the decimal point. For example,

0.0015 m = 1.5 mm = 1500 µm (micrometers).

Time and Speed

The unit of time in the SI is the second (s). Although based on data of atomic physics rather than day length, for most practical purposes, it is the same as the familiar second. The best way to compare speeds is to express them in meters per second (m/s).

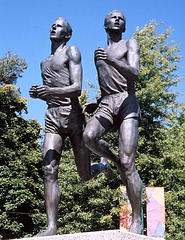

For example, on May 6, 1954, when it was widely believed to be impossible, Roger Bannister (Fig. 2-1) ran a mile on the track in less than four minutes. Let us calculate his speed in m/s. First we need the number of meters in a mile:

5 280 ft/mile X 12 in/ft = 63 360 in.

63 360 in/ 39.37 in/m = 1 609.347219 m

The mile is an obsolete unit. In the Olympics, and most track meets, the nearest equivalent is the 1500 m, referred to by ignorant sports writers as "the metric mile". In June 2003, Regina Jacobs, at the US championship meet, ran the fastest women's 1500 m of the year, in 4:01.63, just a little over four minutes.

Exercise 2-1. Calculate the speed of Regina Jacobs.

The result shows that Sir Roger was about 8 percent faster. For most running events, world record times for men are about 10 percent less than those set by women. Data on other species indicate that humans are not the fastest species afoot.

Exercise 2-2. Racehorses and dogs have been timed over measured courses. Using the conversion factor above, calculate the speed (m/s) of the greyhound Busy Bea when running 5/16 mile in 30.71 seconds. Also determine the record speed of Secretariat in the 1973 Kentucky Derby, 1¼ miles in 119.2 s.

These speeds are similar, and much greater than those of the best human runners. Bursts of speed of some wild animals have been reported in miles per hour.

Exercise 2-3. Determine the speeds in meters per second of the pronghorn antelope, Antilocapra americana, 61 miles per hour; and the cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus, 70 mph. (1 hour = 3 600 s)

Predators must be able to catch fast-moving prey. Drive your Jaguar to the start of the 5-km road race, double-knot your Cheetah shoes, and run like a predator.

With the aid of mechanical devices, humans can move much faster than a cheetah. The first steamboat built by Robert Fulton, however, did not move with blinding speed. In 1807, this boat went from New York City to Albany, about 150 miles up the Hudson River in 32 hours. This makes the average speed 2.095 m/s. A good distance runner can cover 100 km in less than 6 hours, with average speed more than twice that of the steamboat.

Bicycle speeds are a different story. In 1904 at the St Louis Games, a cyclist from Newark, NJ won Olympic gold in the five-mile race with a time of 13:08.2. Equipment and training have improved greatly since then. In the 2003 Tour de France, Lance Armstrong, the five-time winner, completed one leg, Pornic-Nantes, in 54:19. The newspaper reported the distance as 30 miles and the best speed as 33.78 mph, but these numbers would make no sense in France, or among educated people anywhere in the world. A little calculation shows that the distance was actually 49.0 km.

Exercise 2-4. With the times and distances from the preceding paragraph, find the speeds of the two cyclists.

The speed of the Concorde as it crosses the Atlantic is 581.2 m/s, which is called supersonic, because the speed of sound in air at 0o C is 331.6 m/s.

These are relatively low speeds compared to the space shuttle, with an orbital speed of 7 823 m/s, hard to imagine, but still well below the ultimate speed, the speed of light:

c = 3 X 108 m/s.

108 is a better way to write 100 million, 1 with 8 zeros after it. 103 is 1 thousand, 106 is 1 million. Powers of ten are very useful in dealing with large numbers. The speed of light is so much greater than the speed of sound that the distance of a lightning flash can be estimated from timing the sound of the thunder. Each 3 seconds means 1 kilometer distant, and each 5 seconds about 1 mile.

Exercise 2-5. A timer at the finish line of a 100-m race reports the winning time as 10.19 s. However, she did not see the flash of the starting gun, but started the stopwatch when the sound reached her. How much time should be added to get the corrected time?

For national record purposes, the runner in a hurdles race cannot be aided by a following wind more than 2 m/s. At a June 2003 championship meet, the announcer said that this is equivalent to 4.5 mph. Is this correct?

Exercise 2-6. One meter is a long distance for some small animals, and their speeds vary greatly. Calculate the speed of a spider Tegenaria atrica that moved 3.0 meters in 5.74 seconds, and the speed of a garden snail Helix aspersa (Fig. 2-2) that crawled 1.0 meter in 74.6 s.

The speeds discussed above, and a few others, are listed in Table 2-1.

A good project is to select animals or machines from this list, and compare speeds by means of a bar graph with an exponential scale. Decorate with drawings of a lizard or a flying machine, for example.